About Phil Parkes Maille

Conservation | Bespoke Historic Maille

I am Professor Phil Parkes, an accredited Conservator-Restorer. I have been based in Cardiff in the UK for three decades. I have worked with National, regional and commercial archaeological organisations and museums carrying out on-site and post-excavation conservation for publications and display. Objects conservation has included Bronze Age burial vessels, waterlogged Iron Age structures from Goldcliff, Roman metalwork and coin hoards, medieval glass and finds from Haverfordwest Priory and waterlogged leather objects from The Newport Ship.

I taught practical conservation, decision making and analysis of heritage materials to undergraduate and post graduate students at Cardiff University for over 30 years.

Background to my maille making

So how did this start? This mail shirt from Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery had been in the Cardiff University Conservation labs for a number of years. Back in 2018 @kristjanavilhjalms was assigned the shirt as a student project and started looking at how maille was manufactured with a view towards using traditional techniques to repair the damaged areas of the shirt. I have always been interested in arms, armour and such like (RPGs such as D&D to blame…) and the manufacturing techniques looked fun. But where to find out more?

Luckily, also based in Cardiff was a great source of information – @marcushaleus who runs @capapie. Mark has been making maille for many years and together with Master Maille maker @nicholaschecksfield has produced a very informative documentary on the process for English Heritage. As a conservator I enjoy the challenge of intricate work and watching this film and seeing how painstaking the process was, this really appealed to me. I needed to find out more…

My Blog and Instagram account is detailing my progress from November 2018 – making tools, experimenting with different techniques, and the maille projects I have been working on.

My ultimate aim is to make a copy of this standard from the The Wallace Collection. The standard is number A9 in the collection and dated to the late 15th century. The collection website describes it thus:

The collar of this ‘standard’ or neck defence is a virtuoso demonstration of mail-making skill. It’s very small, heavy links are so tightly woven that almost no light can be seen to pass between them. The gaps between the links are also so narrow that the links themselves cannot rotate, but are held fast by their neighbours. The link rivets therefore remain in neat, straight rows, just as they were when the piece was made.

Such mail was not only good protection against the cutting edges of sharp bladed weapons, it could also stop the thrust of a dagger or the point of an arrow. Since wounds to the throat would usually prove rapidly fatal, it was important to find robust armour for the throat which was also comfortable to wear. Such dense mail was an excellent solution to the problem.

The mail which makes up the mantle of this piece has been constructed using larger, lighter links, making the material much more flexible but also less protective. This is a good example of how the makers of armour always had to balance protection against comfort and mobility. The mantle appears also to have been made by a different, less skilled craftsman than the master who made the collar. The collar could have been made earlier, and was fitted with the present mantle later in its working lifetime. Alternatively, a master mail-maker may have made the collar and then passed it to one of his assistants for finishing.

From reading the above this sounded exactly the sort of challenge I was after – fiddly, intricate, looking like it would take weeks/months to do…

The place to start was the collar. The advice from Nick Checksfield was that the only way to make this was one link at a time. It was time to do some research and experiment with links of different sizes.

How to make the rings? The English Heritage ‘How to make Chainmail’ film was a great starting point. I hadn’t really considered the whole process before. Making the rings from a spring for starters was a surprise! The spring is made by coiling annealed iron wire around a mandrel (another fun fact, the overlap is always in the same direction) of the size that you want your ring to be. The rings are then cut with an overlap. To do this I modified a pair of side cutters by grinding a hole in the cutting edge so that they would skip over the first bit of wire and cut the piece behind.

The wire needs to be softened after this process, by heating to red hot and allowing to cool using a blow torch as I don’t have a forge available (yet…). Once cool the overlaps are flattened. For larger rings I use a hammer and anvil, but I have found that for these very small rings a set of tongs gives a more consistent result and a shape very similar to that of the A9.

After flattening, we have to soften by heating again. The rings are then ready for drifting. This is where we make the hole for the rivet. The holes are usually round for earlier mail, but for 14th / 15th century European mail wedge riveting is much more common and this is what can be seen on the A9 standard. The drift is a small tool of hardened steel with a wedge-shaped point and is used to gently hammer a hole through the overlap. The important thing here is that it does not punch out the hole (like a holepunch), but the material from the overlap is pushed to the side.

Wedge shaped rivets are cut in order to join the overlaps together. I have included a scale in most images to give you a better sense of the size of these rings. These rings are made from 1mm diameter wire wound on a 3.3mm mandrel (just over1/8″) and the wedge rivets are 1.8-2mm long.

How long does this take? Well after making a couple of thousand rings so far I can now make about 150 rings in 2.5 hours and I estimate I will need about 2,500 rings for just the collar section alone!

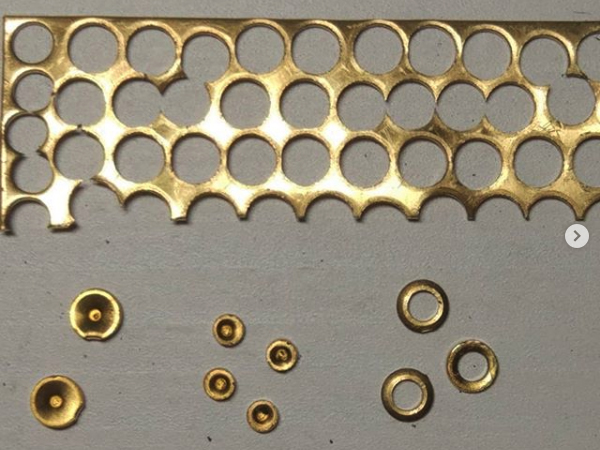

The first two rows of the collar are copper alloy (known as lattens). The first row are solid rings, probably made by punching out of a sheet, while the second row are riveted rings of the same style as the remainder of the collar. The row of solid rings are of a smaller diameter than the riveted as this helps to ‘stiffen’ the top of the mail.

In order to make the solid rings I have followed the original process – punching out of a sheet of brass. However, rather than use punching tools / dies I decided to cheat a little with a Kennedy punch. I was able to punch out discs and then punch holes in the centre of the discs to produce solid rings. I was trying to punch as many discs as possible from my sheet of brass – you can see in the picture a couple of the discs with ‘bites’ taken out of them by punching too close. The rings have a distinctive concave shape from the punching.

The solid rings were threaded onto a wire and the riveted rings looped through them before inserting rivets and closing them (more on this in the blog). Initially I used brass rivets, before I read that iron rivets were used in almost all cases. Doh! Back to punching out more rings and redoing with iron rivets…

How long to make the collar? Well, it has to go around my neck and from looking at modern standards many of them have padding, although there does not seem to be any surviving evidence of this on the original standards (can anyone out there confirm this?). I added a little bit on to allow for padding if necessary. In total I needed 170 rings to get a length of 17½”. How long did this all take? Well I am documenting time taken to manufacture and these first two rows took 16½ hours… Two rows done, I am trying not to think too much about how many are left.

For further updates, please have a look at my Blog